If you’ve ever wondered what the ancestors of Pangu, Nuwa, and Yuhuang Shangdi were like, you’re not alone. In China, there are many myths and legends surrounding these mystical beings. Despite their esoteric nature, many people still worship these ancient gods.

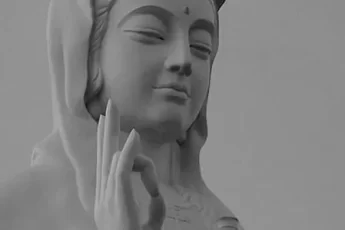

Nuwa

In Chinese mythology, the chaos deity Nuwa is a deity of nature and chaos. During the Flood, Nuwa’s Flood tore a hole in the heavens and killed most of humanity. The broken pillars of heaven and earth caused chaos, fires, and ferocious animals, leaving a permanent record of these events on Earth.

Nuwa is one of the most popular goddesses in Chinese mythology. She is also associated with marriage and fertility. There are two versions of her origin myth, according to which Nuwa created mankind either by sculpting them out of clay or by repopulating the world after the flood.

Although the protagonist and Nuwa first meet in Minato, Da’at, Nuwa massacres the angel followers of Bethel in the National Diet Building. Nuwa then assumes the protagonist is the backup sent by Bethel, transforming into a snake. However, the protagonist eventually gains the upper hand over Nuwa, when Yakumo rescues him. Afterward, Nuwa develops an interest in the protagonist and begins to watch the protagonist’s every move.

Pangu

In Chinese mythology, the Chinese chaos deity Pangu is a god of nature who has created everything in the world. He is responsible for the creation of mountains, rivers, and lakes. When he died, his limbs turned into a pillar of heaven, and his eyes, hair, and skin turned into plants and flowers. Eventually, his body was transformed into everything in the universe. His left eye became the sun, his right eye the moon, his protruding parts the earth, and his hair, skin, and muscles became the rivers and the soil field. His teeth, meanwhile, turned into giant stones and his breath became thunder and rain.

Pangu lived for 18,000 years. In that time, heaven and earth did not exist in their separate forms. During this time, the universe was created. Pangu was born within an egg, and stretched its shell to create the earth and heavens. He lived for nearly a thousand years in this egg, stretching its shell.

Yuhuang Shangdi

The Yuhuang Shangdi, the Chinese chaos deity, was first mentioned in ancient literature about 700 B.C.E., long before the time of the Shujing (the Classic of History). This work was the oldest narrative in China, and may have even predated the Greek historian Herodotus by many centuries. While Shangdi’s characteristics are similar to those of a person, he is the only deity that is explicitly referred to in this text.

The best description of Yu Huang came from Henri Maspero, who wrote “The Origin of Yu Huang in the Early Chinese Mythology.” The text was translated by Frank A. Kierman. Yuhuang benxing jing, a manuscript dating from the 12th and 13th centuries, plays an important role in Daoist ritual.

Throughout history, Chinese people have believed in more than one thousand gods, and many of them are responsible for the creation of the world we know today. The first god of Chinese culture, Yuhuang Shangdi, is said to have created the universe and overseen the lives of humans. He is commonly depicted as a man with long hair, a full imperial garment, and a ceremonial tablet.

Long Wang

The Chinese chaos deity Long Wang was a member of the brotherhood of gods known as the Four Dragons. These gods ruled the four seas and controlled the weather. He ate gems and lived in a great palace under the sea. He received orders from the Jade Emperor.

According to legend, the Dragon King had thousands of descendants, one of whom became the Buddha in the Lotus Sutra. Many early Chinese emperors claimed to be directly descended from the Dragon King, which gave them great power. While Long Wang initially resisted Buddhism, he was eventually won over and became a deity in Chinese Buddhism. Dragons have long been associated with water in Asian cultures, and their imagery is frequently used to represent it. But dragons carry deeper meanings than just being an icon of water.

In Chinese mythology, Longwang represents the yang and yin of nature. He rules the oceans and the weather, as well as the creatures that live in them. He is a powerful deity who uses his powers for the good of the people beneath him. In ancient times, dragons were symbols of Imperial power, and people tried to emulate the Dragon King.

P’an Ku

P’an Ku was the creator of the world. He had a serpent body and a dragon head. His breath created wind and day, and his blood created the elements of the earth and water. When P’an Ku died, his bones and skull were reshaped into mountains and rivers. His teeth became minerals and precious gems. The five sacred mountains of China are said to have been formed from his remains.

This creation myth originated in the 6th century CE and is still practiced in parts of Southern China. According to the myth, the universe began as a formless, chaotic egg. The primordial egg contained all of the elements of the universe, but P’an Ku was born in the middle. This cosmic egg represents the principle of fertility and the duality of being. It also represents the raw material from which creation proceeds.

After separating the opposites in nature, P’an Ku fashioned the world. He was four times larger than any man alive today. He had two great horns on his head and long tusks on his upper jaw. P’an Ku’s body was covered in hair.

Shi-Chi

Chinese mythology features a chaotic deity known as Shi-Chi. He is a dragon-like being with a human face. According to legend, he spawned the human race. He is sometimes accompanied by his half-human brother, Fuxi. These two are sometimes worshipped as the ancestors of humankind.

Chinese mythology is a collection of myths, legends, and religious traditions. Many of them have been passed down orally for centuries. They include creation myths and tales, stories about gods and demons, and a variety of other stories that surround the origins of Chinese culture.

Many mythological gods represent actual historical figures, and embody popular, classic virtues. In addition to the Chinese deity Shi-Chi, there are a number of gods that embody classical virtues. One of the most famous of these is Bao Zheng, who was a magistrate during the Northern Song Dynasty. He was known for his integrity and relentless pursuit of justice. His name means “justice”, and he is considered a god of justice. He is also the avatar of Wen Chang. In his sleep, he judges the dead as Yan Luo Wang.

In Chinese mythology, Shi-Chi is one of the most powerful deities. In ancient times, he had a mighty presence. In fact, the deity was so powerful that he could destroy the world. It is believed that the Chinese deity was also responsible for the Great Flood. A lot of people still worship him today.

Hou Yi

Hou Yi is one of the most iconic figures in Chinese mythology. He is both a hero who saved China and a tyrant who wanted to live forever. His “realistic” character and morally grey personality has made him an enduring figure in Chinese mythology. His symbolism includes being the patron of Chinese archers, as well as the protector of the sky. His love for his wife, Chang’e, is one of the most powerful love stories in Chinese mythology.

During Yi’s crusade in the north, he faced Jiuying, the god of the unruly river. This nine-headed bird flipped over boats and flooded lands. Yi steadied himself and killed the savage creature, and then headed north to the Yellow River with its rolling mountains of waves.

Hou Yi is a powerful and dangerous deity in Chinese mythology. His name refers to the goddess who bestowed upon him immortality. The goddess Xiwangmu, also known as the immortality pill, gave him this power. According to legend, he later gave this power to Chang’e, whose immortality is symbolized by the moon.