This article is about a 19th century Chinese deity bronze scroll that was offered for sale at a Sotheby’s presale. We also discuss lacquerware, embroidery, and a folding screen from the Song dynasty. The 19th century Chinese deity bronze scroll was probably embroidered by male embroiderers from Guangzhou or the nearby town of Chaozhou.

Sotheby’s presale estimate for 19th century chinese deity bronze scroll

A 19th century Chinese deity bronze scroll is estimated to sell for more than the presale estimate of $415,000, which was set at $475,000. The scroll was made in the late Qing Dynasty and is believed to depict the Sun Goddess. The scroll has a high-quality finish and is in excellent condition.

The Sotheby’s presale estimate for the 19th century Chinese deity bronze scroll is $478,000-$493,000, depending on condition. The Chinese bidder purchased it for an undisclosed buyer. The piece is the longest scroll in the world, measuring 45 feet in length. It has been in the family for more than 80 years and has sold for a record price. The seller called it a “fairy tale” for the family.

The Chinese bidders were smitten by this work and nearly doubled its presale estimate. The piece features a poem by the emperor Qianlong as well as a date corresponding to 1776. While Sotheby’s presale estimate for the 19th century chinese deity’s bronze scroll was too low for the item to be a historic imperial heirloom, Chinese bidders were willing to ignore the object’s spoofy appearance.

Another item sold for more than the presale estimate: an antique gilt-bronze figure of the Chinese Buddhist deity, Cintamanicakra Avalokiteshvara, sold for $2.1 million. The seller brought the piece to a recent Antiques Roadshow appraisal event in St. Louis, Missouri. The work was originally purchased at a garage sale for $75-100.

An “archaic” bronze vessel of the Shang Dynasty was estimated at $8,000 to $12,000, but the bronze vessel sold for $68,500, six times the presale estimate. It is believed that the bronze vessel was considered a preeminent symbol of state authority.

The Reverend Richard Fabian Collection of Chinese Paintings and Calligraphy III also included a modern work by Huang Binhong. The work sold for more than double its presale estimate, and is estimated to fetch up to $625,000.

The handscroll was previously exhibited at the University of Michigan Museum of Art in Ann Arbor. It is an important work by one of the greatest artists of the Ming Dynasty.

Song dynasty embroidery

Song dynasty embroidery on a 19th century Chinese deity bronze scroll is a rare and magnificent example of Chinese tapestry art. It was likely created by a master tapestry weaver from the southern Song period named Shen Tzu-fan. The scroll was discovered in Manchuria and returned to China in 1954. It was named Qingming shanghe tu or Qing Ming Shang He Tu. Its discovery has led to numerous attempts to date the scroll to the twelfth century.

This 19th century Chinese deity bronze scroll, also known as a ‘Ten Thousand Buddhas’ scroll, has elaborately embroidered motifs and features of the God of Prosperity. The deity is often pictured holding a treasure vase or holding a child. The imagery is much more formalized during this period than it was in earlier periods. Embroidery on these scrolls often focuses on presenting a blessing for long life.

In addition to the Chinese deity bronze scrolls, Song wares also exhibit exquisite embroidery. These wares were produced in the Henan province. Most of the surviving examples date back to the Tang dynasty. Song-era products included pillows, vases, wine jars, and vases. The body of the ceramics is a grayish-white stoneware with a white slip glaze. The decoration appears under the glaze and is usually floral in nature.

Embroidery has been practiced for thousands of years in China. In fact, embroidery began in the Chinese culture as early as 2200 B.C. Silk embroidery was used to decorate clothes and other objects. The technique even evolved into an art form. Silk embroidery also served as a method of representing calligraphy and paintings.

After the death of a parent, the Chinese would go into a period of mourning, a process referred to as qi. As a result, a lot of pictures and ceramic designs are dedicated to honoring a deceased parent. A traditional transverse held flute, which originated in Tibet two thousand years ago, is also a melancholy instrument, with its six holes representing the netherworld. It is often used in opera as accompaniment for apparitions.

Embroidery techniques used during the Song dynasty include the Gold-Couching Stitch and the Thread-Couching Stitch. The former involves using gold or silver-wrapped threads to create an outline and uses a similar color for the rest of the embroidery. The latter technique is used to render a variety of objects, such as pine needles, grass, and fan-shaped needles.

Song dynasty lacquerware

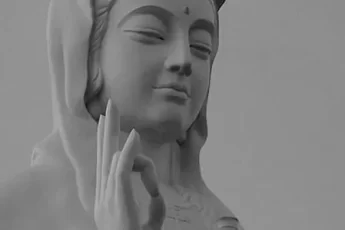

This fine example of Song dynasty lacquerwork depicts a seated woman with a benevolent expression and her hands clasped in front of her chest. She wears a voluminous robe that falls to the top of her ruyi-toed shoes. The robe is secured with a court belt and a long sash tied in a bow between her legs. The robes’ border is engraved with dragons chasing flaming pearls. The woman is wearing a ribbed headdress with a hairpin and a pendant in the shape of a lock.

The scroll depicts a female deity. This scroll is dated to the Northern Song period and was used to commemorate a deceased person. Other items of the dynasty include a celadon tripod, which dates to the late 10th century, a small jar made of “qinbai” porcelain, a personification of the Chinese zodiac, and a funerary porcelain figurine from the 12th century, found in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province.

Chinese lacquer experts were renowned for their skill in carving and applying lacquer. These artists were able to carve images and floral patterns through the thick layer of red lacquer. Some of the best lacquer artists of the Song dynasty were Yang Hui, Zhang Cheng, and Yang Mao.

By the middle Qing dynasty, Chinese lacquerware had become increasingly elaborate and complex. Some wares were covered with up to 200 layers of lacquer, which was a time-consuming process requiring a high level of skilled labor.

Another example of Song dynasty lacquerwork depicts a Chinese deity seated in a landscape. It is composed of two tiers, each of which is divided into a base and a top. The interior is decorated with wide borders and painted in black lacquer.

Song dynasty folding screen

The Song Dynasty folding screen with 19 century Chinese deity bronze scroll has a history of discovery. This work was found in Manchuria after the Second World War and returned to China. Chinese scholars have since dated this work to the twelfth century. It is considered the oldest known scroll from the Song dynasty.

The artistry of this screen is unique. It features the works of Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769-1825) and Utagawa Toyokuni II (1777-1835) as well as the work of Shunkosai Hokushu (act. 1810-1832).

The children in the screen are dressed in traditional Chinese clothing and are playing in a garden setting. The screen is framed and bordered with silk. The screen is made of wood and is a great decorative piece. If you are in the market for a Chinese antique, then this is the one for you.

Artists outside the literati-scholar tradition were also gaining renown. Some of them created paintings for financial gain. Ma Quan was a popular painter who depicted everyday objects and was not a member of the formal schools of painting. He was influenced by Song dynasty paintings and modelled his brushwork on them. Yun Bing, the founder of the boneless technique, is thought to have first invented the technique during the Tang period. Yun Shouping, a descendent of Yun Bing, continued it.

The display includes many works of art from the Song Dynasty. One such piece is a phoenix vase from the Summer Palace in Beijing. The phoenix was a popular symbol in the ancient Chinese court. It was often used in conjunction with the Empress and symbolised royal unity and coupling. However, the phoenix in this piece raises questions about its history.