There is no hierarchy of Chinese deities, a key difference from western religions. Most western religions have a single supreme god, with other deities such as angels and archangels below them. In addition, these religions have heads of district, region, or denomination. In contrast, Chinese deities don’t have any hierarchy, and they are generally considered a single entity.

Xiwangmu

The Chinese deity house Xiwangmus was originally a ferocious monster, but over time, it was transformed into a deity, losing her beastly attributes to become more human-like. Xiwangmu’s current form is more like an elderly woman, but her powers are still the same. She is believed to direct the ‘catastrophes of the sky,’ causing natural disasters.

Xiwangmu is an important figure in Chinese mythology. During ancient times, she ruled the west and the east, a union of the two deities created humanity. She is also considered to be the most powerful female deity in the Chinese pantheon, ruling over the lives of all living creatures. She presides over both life and death, and is said to protect women over 50. In traditional art, Xiwangmu is depicted as a beautiful young maiden, while in early texts, she is described as an ancient woman with snow-white hair.

Xiwangmu is the controller of the Five Shards and Grindstone constellations. The deity is represented as sitting on a stool, with a head ornament and a staff. In myth, Xiwangmu receives nourishment from three birds, located in the south, and north of the Kunlun mountains. Xiwangmu’s name translates as “Western Grandmother” or “Spirit Mother of the West.”

According to Zhuangzi, Xiwangmu is one of the highest deities, seated on a spiritual western mountain range. Moreover, the Xiwangmu is connected to the west and the heavens. She also has a womb.

Xiwangmu is the only Chinese deity in the pantheon to have direct communication with the heavens. Her peach tree was said to act as a bridge between heaven and earth. This role gave the emperor the Mandate of Heaven, which was considered his divine right to rule. The first Emperor to claim this title was Emperor Shun of Shanxi.

The Chinese deities were very important to ancient Chinese culture. Different deities were more prominent at certain times.

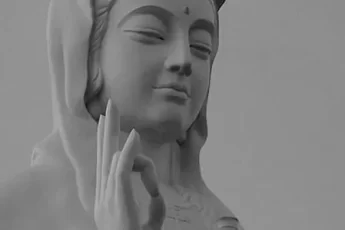

Guanyin

Guanyin is the patron goddess of the poor and the unfortunate. She is also revered in coastal areas of China as a protector of sailors and fishermen. She is the goddess of fortune and agriculture in some parts of China. This deity can take on many forms in different cultures, and her worship has spread throughout the world.

Guanyin is the most popular deity in East Asia, and her name translates to “she who hears the cry of the world.” She is also known by other names, such as Kuan Yin, Kwan Yin, and Guan Zi Zai. In Chinese lore, she is most often depicted as a female.

Despite her incarnation as a Buddhist goddess, Guanyin is also an influential deity in Theravada Buddhism. In fact, statues of Guanyin can be found in influential Theravada temples, such as Thailand’s Temple of the Emerald Buddha and Wat Huay Pla Kang. The statues are also commonly found in Asian art sections of world museums.

The cult of Guanyin is closely linked to art, which has been one of the best ways for the Chinese people to become familiar with her. Aside from the stories of everyday people’s encounters with Guanyin, miracle tales about Guanyin serve as an important medium to domesticate her. By depicting real people’s encounters with the goddess, the stories of miracles attest to her efficacy.

Guanyin is often depicted in a regal, white robe. She is often shown holding a vase of pure water or a willow branch. Her crown often depicts Amitabha. Some statues of Guanyin show a young man or woman in a Northern Song Buddhist robe.

Chang’e

The myth of the Chinese deity house Chang’e is said to date back to the 5th century BC, when the Warring States period was still young. Chang’e is said to have stolen the elixir of immortality from Xi Wang Mu, Queen Mother of the West, and subsequently flew to the moon where he became the spirit of the moon.

In Chinese mythology, Chang’e is associated with the Moon festival, which is celebrated on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month. The Moon Festival, also known as the Mid-Autumn Festival, is a time of reflection and celebration. The full moon at this time signals the rising of the yin element in the annual cosmological cycle.

The myth describes Chang’e as the moon goddess who once sat on the throne and looked down on the Earth. She then sacrificed herself to serve her husband and thus save the world from the evil god that was threatening to destroy it. As a result, Chang’e is a well-known goddess in Chinese culture.

During the time of the Jade Emperor, Chang’e lived in immortality in the heavens. However, when Houyi rebelled, he banished Chang’e from heaven and sent him to live as a mortal on Earth. The story of the deity house Chang’e is quite fascinating. The tale is not completely believable, but the fact that it’s a popular legend is an interesting insight into Chinese mythology.

The name Chang’e has many legends associated with her, ranging from an emperor to the mother of the twelve moons. In fact, Chang’e was often confused with another goddess, Changxi, who gave birth to the twelve moons. If the two are related, Changxi’s name may actually be Chang’e’s mother.

The story of the Chinese deity house Chang’e is a tale of revenge. It is said that Emperor Lao gave the immortality elixir to Hou Yi, who then entrusted it to Chang’e. When Hou Yi was away, Chang’e took the elixir for himself. Chang’e then retreated to the moon, where she lives for eternity.

Mazu

The Chinese deity Mazu has been given many titles since she entered the pantheon in the 11th century AD. She is sometimes called the Princess of Supernatural Favor, the Empress of Heaven, the Goddess of the South China Sea, or simply the Goddess of Mercy. Whatever her name, she is a powerful woman who is worshipped for her maternal qualities and ability to protect people.

Mazu was also known as Lin Mo, the marine god, who was said to know weather patterns and announce safe sailing times. Sailors pray to Mazu before setting out and thank her when they return safe and sound. Many tales exist of disasters averted by Mazu. When the weather changed, she appeared to fishermen in red and helped them sail back to shore.

The Chinese worshipped Mazu for her ability to protect people from harm and ill, and her protective powers were well-known and respected. Chinese belief in deities is often characterized by a mixture of fear and respect. People consider deities as personifications of justice, but they also see them as temperamental and potentially dangerous beings. Mazu will only protect those who ask her for help, and she has a long list of official titles, although most believers prefer to call her by her most popular name, Mazu.

In China, Mazu and Guanyin are two popular deities. They are considered by Chinese families as protectors and saviors, and gradually ascended to goddess status with the development of society. Both of these deities are closely related to each other, despite their different roles in Chinese society. While the two are often compared by outsiders, they are actually very different in many ways.

The worship of Mazu is often accompanied by pilgrimages. This is a reflection of the central role of pilgrimages in mainstream Chinese religion. People who worship Mazu do not read texts about her, but they perform rituals and offer incense. Other practices include carrying a sedan chair and cooking food for pilgrims. Some people form small communities to worship Mazu.

Mazu’s refusal to marry was a vow that she made after failing to save her brother, Lin Moniang. According to local legend, Lin Moniang died to avoid forced marriage. This is the basis of the myth surrounding Mazu. In another myth, two demons came to ask for her hand in marriage, and Mazu refused to marry one of them.