What does deity mean in Chinese? We’ll look at Na Zha, Benzaiten, Jurojin, and Xiwangmu. We’ll also look at the different deities of the Chinese zodiac. Hopefully, by the time you’re finished reading this article, you’ll have a better idea of which ones are most important to you.

Na Zha

The story of Ne Zha, or “the deity of the sea,” is familiar to Chinese audiences, who have come to know the character from popular movies and classical novels. The legend begins some three thousand to four thousand years ago, when Li Jing, a military commander in the Shang Dynasty in northeastern China, was eagerly awaiting the birth of his third child. His wife, however, was not able to have a baby after three years and six months of pregnancy.

While this movie does have some adult themes and light violence, it is meant for older audiences. The storyline revolves around a child who is fated to die. Jiao and Wei manage to make the dour storyline into something inspiring, and the film makes an important point about the innate power of a person to overcome adversity.

The story is filled with many interesting characters. Lady Yin was pregnant with Nezha for three years and six months. Then, the Heavenly King decided to make Nezha a god so that he could rule the world. But Nezha was not born with the ability to control his destiny.

Benzaiten

Benzaiten is a deity of the Buddhist tradition. Her imagery often consists of a beautiful woman with a biwa. She may also be depicted veiled, adorned in Buddhist halos and other holy symbols. Regardless of the representation, she is known as a goddess of luck and fortune. As one of the Seven Lucky Gods, she bestows good fortune upon those who worship her.

Benzaiten is a mysterious deity who was even more baffling to the Greek Protogenoi. Her aura was so powerful that it resonated throughout the Cosmos and nature itself. People who came into contact with her aura felt the echoes of her presence and were filled with joy.

Benzaiten is a powerful goddess who is worshiped in Shinto and Buddhism. She has supernatural abilities and the ability to manipulate reality through musical mediums. Using her hypnotic singing voice, she can summon people, control the weather, and manipulate objects. Her music can also grant life.

The Japanese also worship Benzaiten. Her name translates to “goddess.” She is also known as Benten. She is the only female in this group and is considered the goddess of love, fertility, and reason. She is usually depicted on a biwa or riding a dragon. She is also associated with the sea and wealth. In addition, she is the patron of warriors and the righteous.

Jurojin

Jurojin is a Taoist deity associated with good health and long life. It is sometimes confused with another Taoist deity known as Fukurokuju, which is said to inhabit the same body as Jurojin. In fact, Fukurokuju and Jurojin are two of the Seven Lucky Gods.

As the god of longevity, Jurojin is often depicted with a bearded man with a long staff holding a scroll of wisdom. According to legend, the god once lived on earth as a Taoist sage. His statues typically depict an ancient man with a white beard, a bald head, and a long, white staff. He also carries a scroll of scripture and sometimes a deer.

The deer also has a special meaning in Japanese. It is associated with wealth, fertility, and longevity. Worshippers often place the god’s statue near water. In Japan, the god is revered on the island of Enoshima. It is said that the god’s presence can prevent earthquakes.

Jurojin is also associated with a treasure boat. The ship is decorated with a gold coin and a Japanese character for good luck. The ship is also decorated with a crane on the prow.

Xiwangmu

Xiwangmu is a deity with many facets. The name itself means deity in Chinese, but the goddess is more than just a name; she also wields power over fertility, longevity, and health. Xiwangmu is a popular god in Chinese mythology, and her worship is a common part of Chinese culture.

She is also associated with the secrets of immortality. She is believed to be the giver of Peaches of Immortality, also known as Pantao. The peaches of immortality only ripen once every three thousand years. In celebration of this, Xiwangmu hosts a feast. Artists in China have made paintings depicting the Peach Banquet.

In the Hai Nei Bei Jing, Xiwangmu is described as sitting on a raised stool and holding a staff. Three green birds also attend her. Her husband was Dongwanggong, the King Father of the East. However, Xiwangmu was much more famous than her husband.

Xiwangmu was a central figure in early Chinese mythology. Many figures from China’s history are said to have had an encounter with her. She is referred to by many different names in art and literature. In addition to Xiwangmu, the goddess is also known as Amah.

Lei Zhenzi

Lei Zhenzi is a deity of the Chinese pantheon who is also known as the son of thunder. This deity is said to have come to earth when a warlord was on his hunt. One day, his dog pawed at the ground and uncovered a small egg hidden among a pile of leaves. When King Wen picked up the egg, the eggshell cracked. Out of the broken shell, a fully grown boy appeared. He had a dark blue skin, a beak and claws, wings, and was crowned with the characters lei, meaning thunder, and zhou, meaning state.

Lei Zhenzi is the half-brother of Zhou Wu Wang. He was also an adept weather magician who gained his power by eating a special almond. During the war, he served as an effective vanguard and earned several notable victories. Many readers consider Lei Zhenzi’s image to be a resemblance to Lei Gong, the Chinese mythological god of thunder.

The legend of Lei Zhenzi dates to around 220CE, and appears to be a product of the influence of Indian deities on China. This deity is a symbol of longevity in the Chinese pantheon.

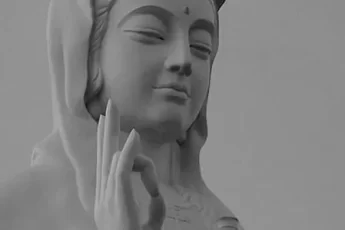

Guanyin

Guanyin is a Buddhist deity revered in East Asia. She is the bodhisattva of observing sounds, and is the most popular deity among Chinese. In East Asian Buddhism, Guanyin usually takes the form of a female, but is also revered as a male. In the West, she is known as Kwannon.

Guanyin’s first appearance in Chinese folklore is described in the Precious Scroll of Fragrant Mountain (also called Xiang Shan Bao Juan). The text is attributed to Buddhist monk Jiang Zhiqi, who lived in the 11th century. According to Jiang Zhiqi, Guanyin was a princess of the Miao Shan clan, but the text contains several variations on this story.

Some Chinese people see Guanyin as a protector of the poor and unfortunate. Others see her as a goddess of agriculture and prosperity. Still others see her as the champion of the disabled and the crippled. In any case, her image is often depicted holding a jar of pure water and a willow branch. The crown on her head is usually a representation of the Buddha, Amitabha.

Guanyin is often portrayed as a beautiful, white-robed woman. While her name is derived from a different word in each region, her images are remarkably similar. In fact, the image of Guanyin in modern times is one of the most popular in Chinese art.

Shang Di

Shang Di means “Supreme Sovereign”. While it is not an exact translation of the Old Testament personal name, the term roughly corresponds to Elohim and Theos. As a result, it is used as a generic term for God. While most Chinese are familiar with this term, many Protestant Christians oppose its use.

Shang Di has several other meanings. It can mean “God.” In the Bible, the term is usually used to refer to the Creator of the universe. In Chinese culture, the word Shang Di is the equivalent of God. The term Shang Di is also used to refer to the YHWH and other spirits.

Although the term Shangdi is most common in the earlier works of Chinese philosophy, it may have evolved over time. Shangdi may have been eclipsed by other deities or abstract philosophical concepts. In the ancient world, Shangdi was known as the Heavenly Ruling Highest Deity. It was often confused with the Taoist Jade Emperor.

Shang records also feature ceremonial inscriptions, family names, and clan names. They are made from bone and tortoise shells. The inscriptions are the oldest known written Chinese.